This year marks the 80th anniversary of important events in the Second World War. Last month, 20 Squadron’s resident historian described the part played by the RAF’s new-found expeditionary radar surveillance and control capabilities in the Allies’ defeat of the Axis powers in North Africa. This article looks at how they contributed to Operation HUSKY, the allied invasion and capture of Sicily, July to August 1943.

The success of Allied operations in North Africa confirmed the thoughts of the air planning staff that radar-based surveillance and control was a pre-requisite for control of the air and future success in combined operations. The Allied decision to invade Sicily as the next move in the war therefore led the radar operators and engineers to consider how they would contribute to their first major amphibious operation mounted from North Africa across the Mediterranean Sea.

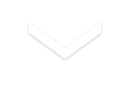

The invasion plan for Sicily – July 1943 (Crown Copyright)

The first task was to limit the use of Axis air- and surface-surveillance radars to provide some security to Allied aircraft and shipping. Thus, in early June, the islands of Pantelleria and Lampedusa were captured, eliminating Axis radars and flying squadrons based there and replacing them with Allied units. In the run-up to D-Day, scheduled for 10 July 1943, Allied bombers struck all known Axis radar sites on Sicily. Finally, on the night of the invasion itself, Wellington bombers from 420, 425 and 426 Squadrons and B-17Gs from the USAAF equipped with a range of radar jamming equipment flew constant patrols off the southern coast of Sicily to disrupt the picture being provided by any remaining Axis radars.

A Wellington of 425 Squadron, pictured in April 1943 (© IWM HU 108262)

Until radar units and operations rooms could be established ashore, aircraft control was accomplished from the Combined Operations Headquarters Ships. There was one for each of the invasion beaches and from their operations rooms the air, land and sea movements of the invasion forces were controlled. The air surveillance and control radars and systems of both the Royal Navy and US Navy were not as well developed as the RAF’s ground-based systems so, in an inspired piece of innovation, RAF radar engineers deployed a radar convoy on the main deck of three LSTs (Landing Ships Tank) which could stand offshore and provide precise intercept control to RAF Beaufighters at night, when the need for radar was at its greatest.

HMS Bulolo – one of the Combined Operations Headquarters Ships (© IWM A23597)

The operations room on HMS Hilary, another Combined Operations Headquarters Ship, photographed on the morning of the landings (© IWM A17944)

A Landing Ship (Tank) of the type used in the Op HUSKY beach landings. To provide seaborne cover, RAF radar vehicles would have operated from the upper deck, where the ambulances with the red crosses are parked in this picture. (© IWM FL7222)

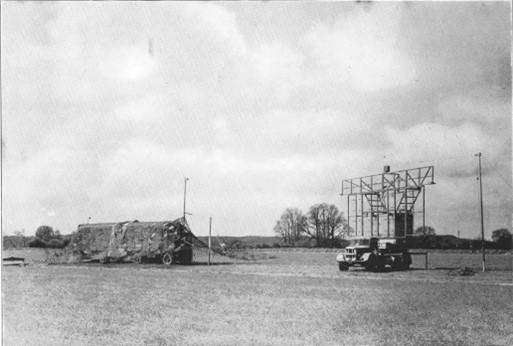

The latter stages of the North Africa campaign benefitted from accelerated production of radar equipment and training of personnel. For the first time then, for Operation HUSKY, there was no shortage of radars, ops rooms and personnel with which to plan! Therefore, for each invasion beach, a balanced radar force was embarked in LSTs to be landed a few hours after the initial assault with the expectation of initial operations late on the first day. A Type 15 radar convoy formed the nucleus, albeit with minimum personnel to reduce shipping requirements. This was joined by two highly mobile Type 6 Light Warning radars and a Wireless Observer Unit to provide visual sightings. The air picture for each beach would be brought together in a Mobile Plotting Room Unit, who would be kept in touch with the rest of the air control system with the assistance of a RAF Signals Section. In all about 100 personnel were involved.

A Type 15 radar convoy deployed for operations (Crown Copyright)

A RAF Mobile Operations Room – this one was used by 13 Squadron in Algeria, but is a good representation of Mobile Plotting Rooms and Sector Operations Rooms would have looked like. (© IWM CNA114)

All the radar units and operations rooms got ashore successfully, with only minor difficulties due to enemy resistance and deep water. First ashore at Cape Passero was the senior controller for the operation, Squadron Leader John Brown; he would become the highest scoring RAF controller in the war and had achieved his 100th controlled victory the previous November in Tunisia.

The view from a ship approaching the coast of Sicily (© IWM CNA1018)

Squadron Leader John Brown, senior controller and first RAF officer ashore at Cape Passero (© IWM NA4404)

RAF personnel landing from a LST on ‘Cent’ beach. This is a barrage balloon unit, but our radar units would have looked very similar during their disembarkation (© IWM CNA4180)

The experience of two radar units are particularly interesting: Number 871 AMES (Air Ministry Experimental Station – the term used for an individual radar station) landed on ‘Bark’ beach near Pachino airfield. Their landing was delayed because the Royal Navy were still shelling enemy positions, but they got ashore at 1100. The tactical situation was too dangerous to move their Type 15 radar inland, so they set up on the beach itself with the Mobile Plotting Room and Air Landing Ground Unit, while the accompanying Type 6s and Wireless Observer Units deployed to nearby hills and commenced reporting. A number of ‘sharp’ Axis air raids that night were described, with typical understatement, as ‘most uncomfortable’.

Number 15051 AMES, with their Type 15 radar convoy, were assigned to support US forces landing at ‘Dime’ beach further west near Gela. They had a much rougher time. They landed at 0830, but the beach was not secure and ‘a certain amount of enemy sniping was experienced’. While waiting for the spearhead of the landing forces to defeat remaining resistance and move inland, members of the unit spent their time aiding injured US Rangers from the initial assault. Unfortunately, the unit’s two controllers were killed when they set off a landmine; Squadron Leader Maurice Allen is commemorated on the War Memorial in Valetta, Malta, and Flight Lieutenant John Gray-King is buried in the Commonwealth War Grave at Syracuse, Sicily.

Squadron Leader Maurice Allen, 15051 AMES (© Copyright 2023 Victoria Allen)

Flight Lieutenant John Gray-King, 15051 AMES (© Copyright 2023 Kevin Moule)

Throughout the remainder of July and the early part of August, radar units and operations rooms were reinforced and leap-frogged their way across the island just behind the advancing armies, until Axis forces evacuated Messina on 17 August.

Lessons were identified which would pay dividends during operations in 1944: for instance, dedicated Air Force Fighter Control ships; and better staffing and equipment for the initial assault wave. That said, the radar surveillance and control system for Operation Husky proved its worth; in the first week after the landings – arguably the most arduous week operating with skeleton staff and little infrastructure – the units detected and controlled successful engagements of over 150 enemy aircraft. Those predecessors of RAF Boulmer’s 19 Squadron, 20 Squadron and BM Engineering Wing who took part in the invasion of Sicily deserve as much recognition as those who served closer to home.