This article is the second this week marking the contribution of Air Command and Control to the Allied operations on D-Day. Today, we look at the design and role of Fighter Direction Tenders, which provided ‘afloat’ Air Command and Control.

‘The importance of these ships to the success of the assault phase of Operation Overlord cannot be over-emphasised.’

Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, Commander-in-Chief Allied Expeditionary Air Forces

The Need for ‘Afloat’ Radars

The amphibious landings in Sicily and Mainland Italy in 1943 demonstrated the need for a wide-area ‘afloat’ air surveillance and control capability to complement the Combined Operations Headquarters Ships. At the time, this need was met by the expedient of lashing one of the mobile Type 15 radars units onto the upper deck of a Tank Landing Ship, correctly referred to as a Landing Ship (Tank) or LST. These vessels were the mainstay of Allied seaborne assault transport. They were capable of open ocean transits and beach landings, with space in their vehicle decks for between 30 and 40 vehicles and accommodation for about 200 troops. In size, they were comparable to some of the ferries operating around the west coast of Scotland today. In the Mediterranean, the Royal Air Force learnt much about operating radars from ships.

American and British LSTs on Omaha Beach after D-Day. © US Navy Archives 80-G-46817

When the Signals Staff at the Allied Air Expeditionary Force Headquarters identified the need for an ‘afloat’ air surveillance and control capability, LSTs were the natural choice. Under project BACCY, three LSTs being constructed in the United States were allocated to become these radar ships. LSTs were routinely not named and were therefore known by their hull numbers. LSTs 13, 216 and 217 were delivered to the Clyde in late 1943, where John Brown Shipbuilders and personnel from the RAF’s Telecommunications Research Establishment set about their conversion to what would become known as ‘Fighter Direction Tenders’ or FDTs.

FDT Equipment and Personnel

In just over six weeks, each vessel was subject to extensive modification work.

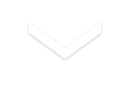

Diagram of a typical Fighter Direction Tender, showing the added equipment (Crown Copyright)

Masts were added to the upper deck to mount antennae for VHF and HF radios, together with radio Direction Finding antennae, and Type 15 and Type 11 radar antennae were mounted on the upper deck.

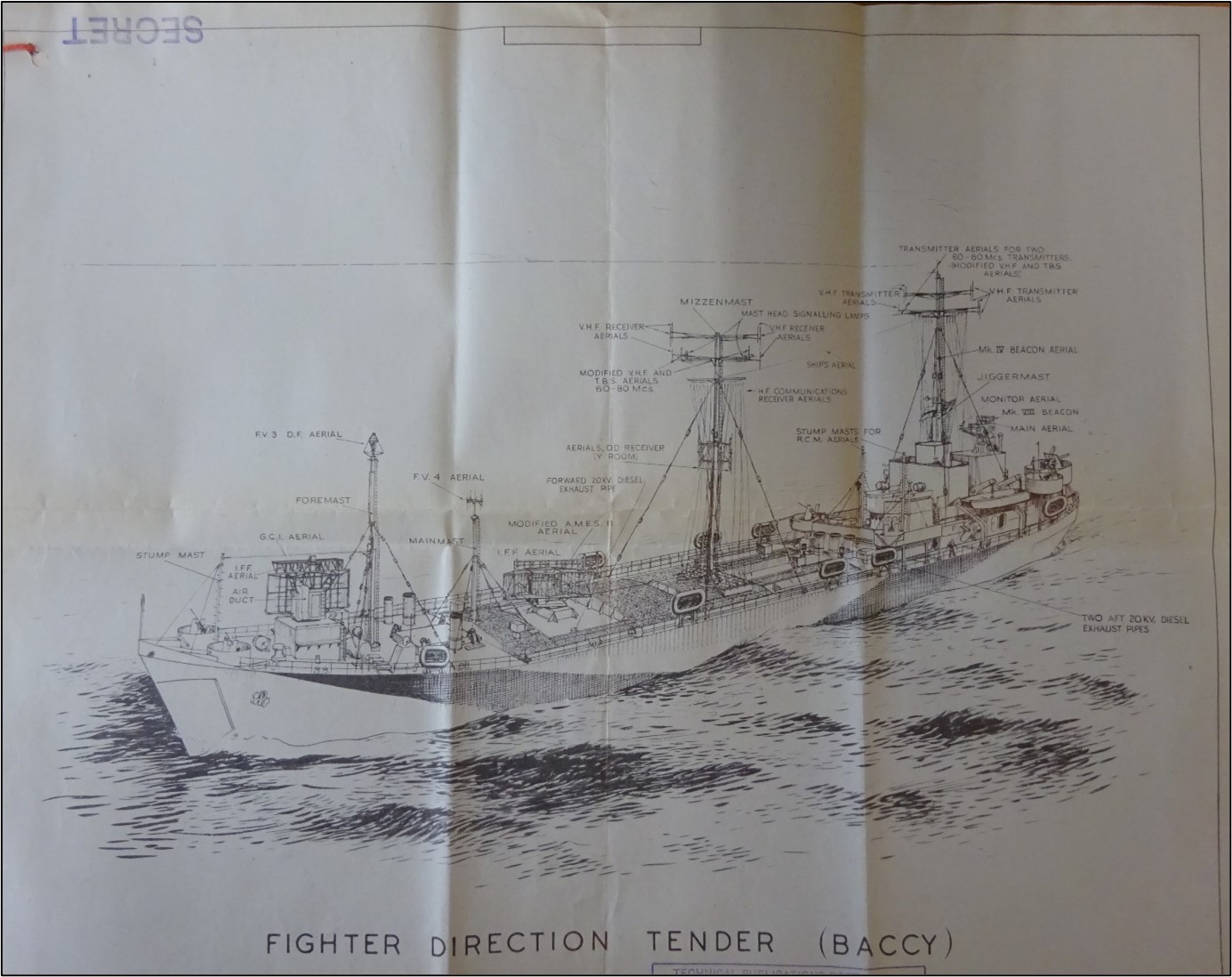

Fighter Direction Tender 217 pictured in Loch Fyne. The two radar antennae are towards the forward end of the ship (Crown Copyright)

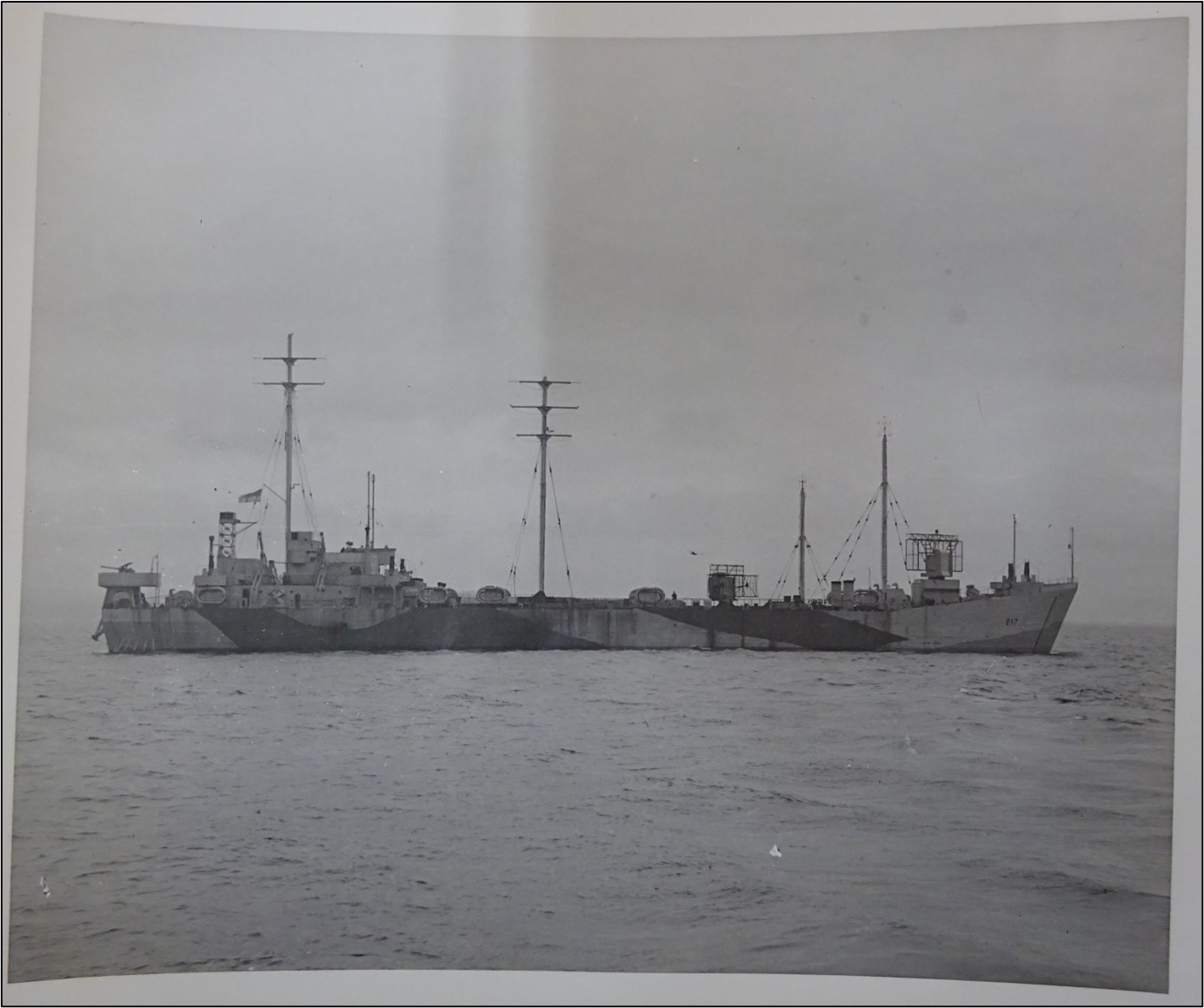

Transmitter and receiver equipment were housed in a new operations complex constructed in the lower vehicle deck. This complex was a series of working spaces dedicated to radar surveillance, track and information filtering, communications, enemy communications intercept (known as ‘Y’), and aircraft control. The operations complex could fulfil the range of roles undertaken by today’s Control and Reporting Centre at RAF Boulmer. In addition, a controller and Royal Air Force observers were posted on the ship’s bridge, adding to the air picture with visual sightings around the ship.

The Filter Room viewed from the Air Control Room, Fighter Direction Tender 13. To the left are the positions for the Filter Officer, Movements Liaison Officer and ‘Y’ Officer. The wall in front carries the ‘Tote Boards’ where information on friendly squadrons and airfields would be posted. (Crown Copyright)

Each FDT was crewed by 100 Royal Navy officers and men, who were responsible for running the ship. They were joined by 164 RAF officers and men to operate and maintain the radars and communications of this floating air command and control centre. The RAF personnel were drawn from regular radar units and operations rooms. They were given additional training, including sea survival, at the Combined Signals School, HMS Dundonald in Ayrshire.

This entitled them to wear the Combined Operations badge.

A Combined Operations badge. © IWM (INS 6096)

Technical and Operational Work-Up

The three FDTs left the Clyde during January and February 1944, after which followed an intense three months of sea trials and operational workup. They each sailed northwards around the UK coast, pausing in the Firth of Forth for technical modifications and spending time off the Humber Estuary in April and May 1944 exercising with the fighters and operations rooms of Number 12 Group, Fighter Command. The RAF personnel, in particular, needed this time to learn about the performance of their radars and radios in their somewhat novel locations, as well as trialling ways to transfer information and orders onto, off and around the ship. Towards the end of May, the ships passed through the Straits of Dover, continuing to exercise with No 11 Group Fighter Command and the mobile radar units of the 2nd Tactical Air Force, who were due to land on the Normandy beaches. This proved to be extremely valuable training and rehearsal for the demands of the operation to come. By early June, all three FDTs were positioned in ports along the south coast, ready for D-Day.

Allied ships marshalling off the Isle of Wight prior to D-Day. The three FDTs would be amongst these vessels. © IWM (A 23720A)

Sailing for Normandy

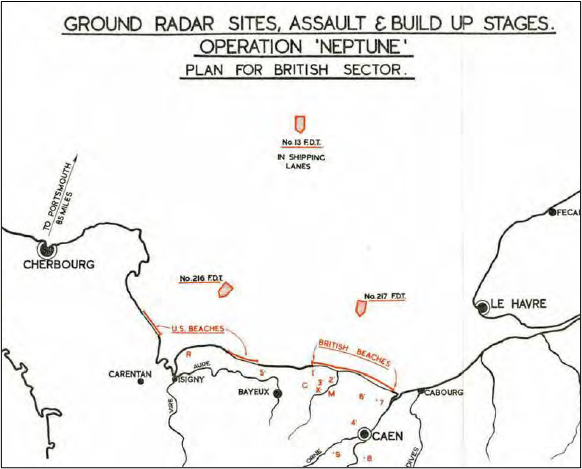

After the famous day-long delay to the launch of the operation, the FDTs sailed from the Isle of Wight on the evening of the 5th June 1944 as part of the Allied convoys. They arrived at their assigned stations by 0400 on D-Day. FDTs 216 and 217 were assigned to the American and British landing areas respectively, and FDT 13 was assigned to the main shipping channel. Positioning of FDTs 216 and 217 required some compromise between air and naval authorities. Their radars would provide the best picture from about 20 miles offshore, as at this range the permanent echoes from the land were minimised. However, this was too far for the naval authorities, who wanted them closer to shore and the large number of warships already protecting the transport vessels. So FDTs 216 and 217 usually operated between five and fifteen miles offshore, accepting the clutter caused by more returns from the land.

The FDT’s positions in relation to the invasion beaches. (Crown Copyright)

Nevertheless each FDT was positioned in such a way that, if one of the others was damaged or sunk, its airspace could be covered by the remaining vessels. As with other ships in the convoys, they sailed in complete radio silence to preserve security, only switching on radars and establishing radio communications at 0725 after the first troops had landed. On arrival off Normandy, each FDT acted as a base for two High Speed Launches of the RAF’s Air Sea Rescue Service; as each FDT was in radio contact with many of the friendly aircraft over the shipping lanes and beaches, they were best placed to ‘scramble’ a High Speed Launch to rescue downed aircrew at sea.

A RAF Air Sea Rescue Service High Speed Launch of the type assigned to the Fighter Direction Tenders for Operation NEPTUNE duties. © IWM (C 4159)

Operations off Normandy

Allied air superiority was such that no enemy aircraft approached until early evening on D-Day, and even those turned back before they could be intercepted. In the days that followed, however, there was plenty of trade. The radars performed well against high- and medium-level aircraft, while the ‘Y’ office onboard was instrumental in detecting German aircraft flying at low-level. The FDTs handed over leadership of the air command and control effort to the deployed Group Control Centre on 14 June, but at least one would remain on station off the Normandy coast for four weeks, with short trips back to the UK for refuelling and revictualling Normandy. The RAF component of the crew were worked hard to maintain surveillance and control – four hours on, four hours off, twenty-four hours per day, accommodated in a ship designed for transits of no more than a few days duration. In the first three weeks of the Battle of Normandy, the FDTs provided radar overwatch to thousands of Allied sorties by day, controlled 419 night-fighter sorties and were instrumental in friendly fighters destroying 76 enemy aircraft.

The Sinking of FDT 216

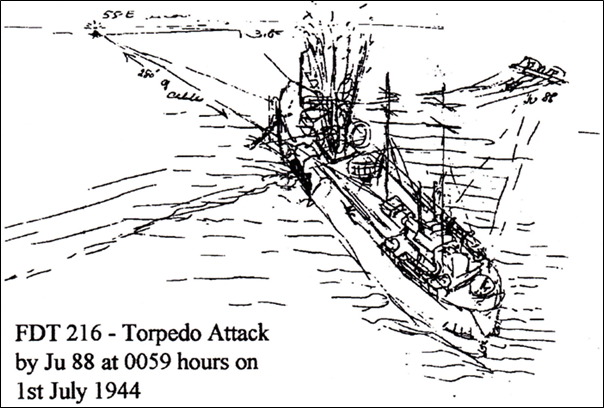

Their successes off the Normandy beaches, with enemy ships and aircraft never out of range to the east, would ultimately come to an end. As the ‘ashore’ radars came online, FDT 217 was withdrawn to the UK on 23rd June 1944, followed by FDT 13 on 30th June 1944, leaving FDT 216 providing ‘afloat’ coverage off Le Harve. At 0100 on 7th July 1944, FDT 216 was torpedoed by a Junkers 88, flying 20 feet above the sea and undetected by either by the FDT or HMS Burdock, her escorting corvette until too late to take action.

A sketch of the loss of FDT 216 from the official report on the incident by HMS Burdock. (Crown Copyright)

Most of her crew, and the ship’s dog (!), were rescued HMS Burdock, but five RAF radar personnel lost their lives in the initial attack. They were lost at sea and are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial:

Corporal George Logan,

LAC James Gaughan

LAC Ronald Peckham,

AC1 John Ferguson

AC1 Thomas Rolt.

Afterword

As the ashore air command and control system became firmly established in Normandy, the requirement for the FDTs gradually decreased. FDT 217, having been on station continuously for seventeen days since the invasion was withdrawn to the UK on 23rd June 1944. Her crew were given leave as plans were developed for her modification for service in the war in the Far East. When FDT 216 was sunk, FDT 13 was in reserve off the south coast of England. The Signals staff decided not to replace FDT 216 off Normandy, and FDT 13 sailed instead for the Mediterranean on 18th July 1944. Stops in Gibraltar, Bizerte (Tunisia) and Naples were followed her performing her air surveillance and control role in Operation DRAGOON (Allied landings in the south of France) and Operation MANNA (Liberation of Greece). FDT 217 was being refitted in London and FDT 13 was sailing back to the UK when the Second World War ended in August 1945.

References:

RAF Air Historical Branch Study, Signals Volume IV, Radar in Raid Reporting.

The National Archives: A Report on the Role and Operation of British Headquarters Ships and Fighter Direction Tenders in the Assault on the Continent of Europe, June 1944, Operation “NEPTUNE”, TNA AIR 37/1439.

The National Archives: “Baccy” Fighter Direction Tenders, AVIA 13/1143.

The National Archives: FDT 213 Operations Record Book, AIR 29/509.

The National Archives: ‘Operation “OVERLORD” – Fighter Direction Ships’. DEFE 2/1072.