In this final article marking the contribution of Air Command and Control to the Allied operations on D-Day, we look at the mobile radar units which landed on the invasion beaches on D-Day and their courage in the face of adversity.

To complement the Fighter Direction Tenders afloat, the Operation NEPTUNE air plan called for mobile radar units to establish an air command and control system ashore in Normandy as soon as possible after the landings. Fortunately, the Royal Air Force had gained plenty of experience in establishing and operating mobile radars, having already done so for the North African campaigns of 1941-42, and the Sicily and Italy campaigns of 1943-44. By this stage of the war, the training system and radar and radio production had caught up with demand and there was no shortage of trained personnel or equipment.

The Operators and Technicians

Personnel for operating and technical duties on radar units destined for Operation OVERLORD were volunteers for ‘special and hazardous duties’. Most followed the same pathway during 1943 and early 1944: Units were brought together at the Royal Air Force Stations Chigwell and White Waltham, where their expeditionary equipment, radars, radios, accommodation, and vehicles were issued. Many units would receive technical training on their equipment at RAF Renscombe Down, Dorset. All would attend the Combined Operations Course at HMS Dundonald, Ayrshire, where their fitness was improved, and they were trained in seaborne assault, waterproofing vehicles and ground defence activities.

Combined Operations Training at HMS Dundonald, Ayrshire. © Imperial War Museum, A13227.

Units would then spend many weeks moving around the UK, learning to operate their radar convoys ‘in the field’. Setting up and taking down of both the technical and domestic equipment were practised again and again, and unit personnel cross-trained, particularly in driving the full range of unit vehicles. As 1943 turned to 1944, the radar units started exercising with their Group Headquarters, simulating the operational task ahead in Normandy. By the time June 1944 came, our mobile radar units and their Group Headquarters were highly efficient in amphibious and mobile land operations.

Pictures from an unidentified RAF convoy practising mobile operations in the south of England. These scenes would have been well-known to the mobile radar units training for the invasion of Europe. © Imperial War Museum, CH12801, CH12806 & CH12808.

The Radar Units and their Equipment

Three Royal Air Force Groups were formed to support Allied operations in Normandy. Numbers 83 and 84 Groups were assigned to the Second (British) and First (Canadian) Armies respectively, while 85 Group would provide defence of the beaches, ports and other rear areas. Each Group would have its own Control Centre, equivalent to a Sector Operations Room in the UK, directing and managing the air battle in its airspace. The air picture for these Headquarters would be generated by a range of mobile radar units, who would report their radar picture and, in turn, control friendly aircraft where required. There were a variety of radar sets in the units. Each set could be used for surveillance and control in a general sense, but their individual frequencies, antenna pattern and support equipment made different sets suited to different tasks.

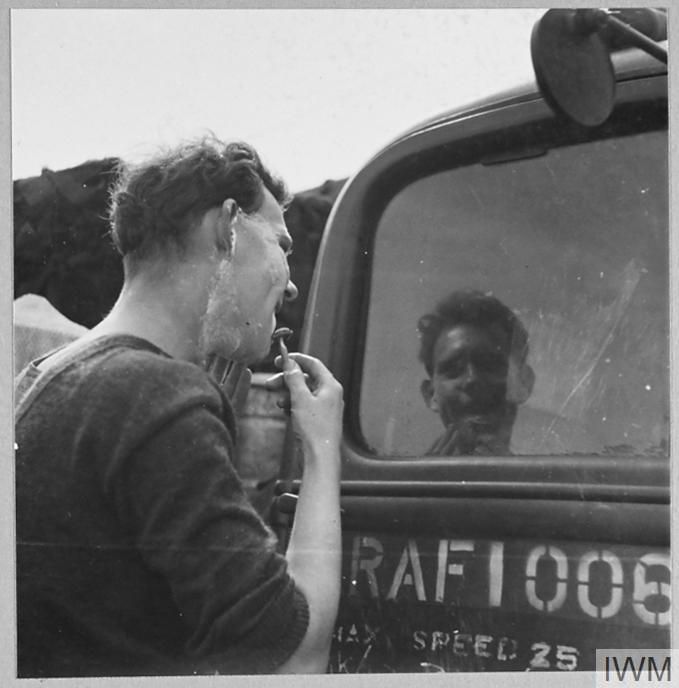

A Type 15 radar convoy. Camouflaged receiver and transmitter lorries to the left, radar and radio antennae to the right. (Crown Copyright)

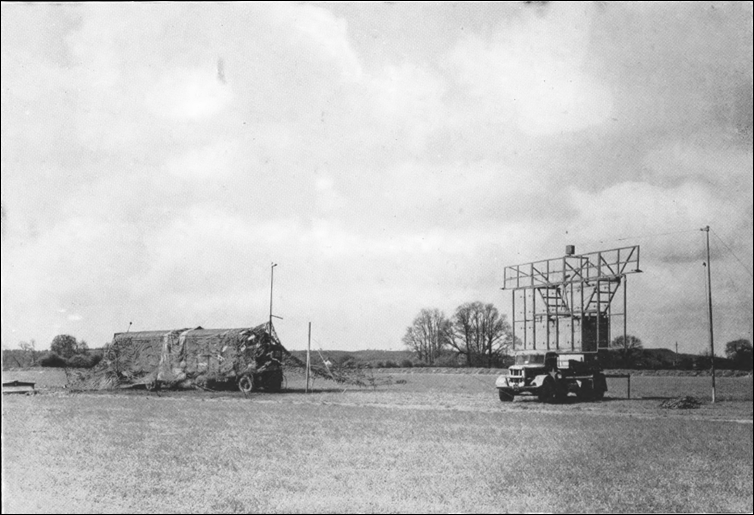

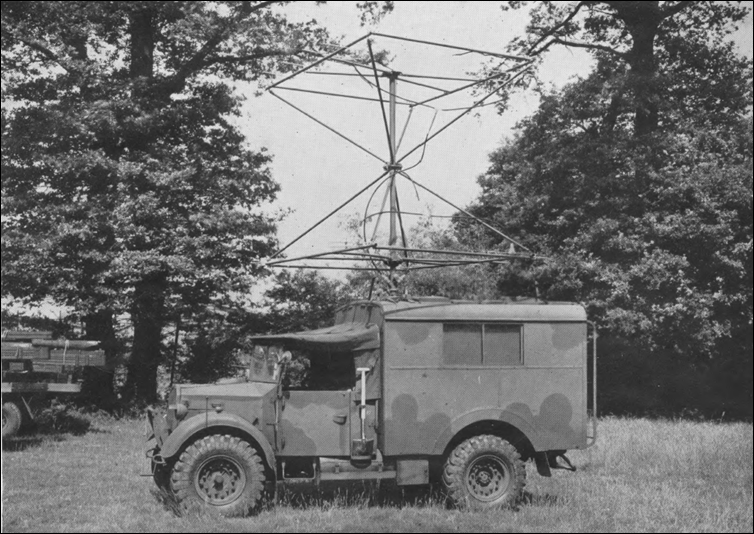

For instance, the Type 15 radar had a wide beamwidth, which was not ideal for close control, but it had good height finding. By contrast, the Type 11 had a narrower beamwidth and longer-range detection, but the vertical beam pattern meant that aircraft were often lost for periods of time. To overcome this problem, it was often operated along with a Type 13 radar, specifically designed for height finding. The Type 11 also operated on the same frequency as the enemy radars and so was an excellent alternative in the event of enemy radar jamming. Most mobile radar units had all three types and comprised 27 vehicles. The Type 6 ‘Light Warning’ radar had less performance than either the Type 11 or Type 15, but was extremely mobile, comprising two trucks, and designed to gap-fill forward coverage from a mile or two behind the front line.

A Type 13 height-finding radar. The antenna would rotate through 90 degrees for travelling. (Crown Copyright)

A Type 6 ‘Light Warning’ radar. Although it lacked the range of the larger sets, its mobility made it extremely useful just behind the front lines. (Crown Copyright)

The Air Command and Control Organisation in Normandy

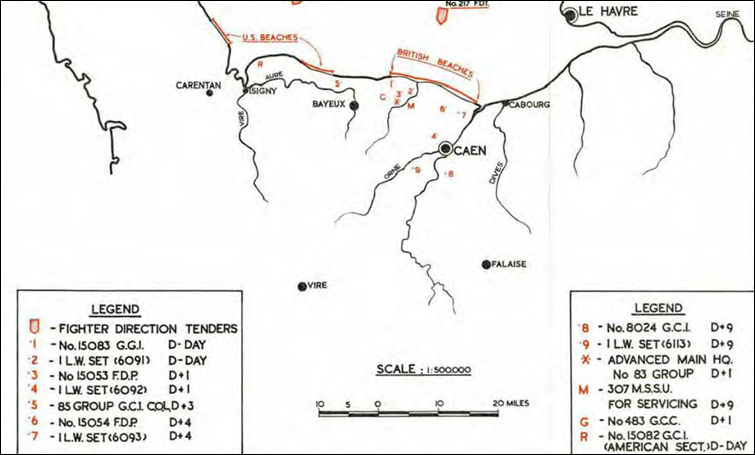

The final plan for air command and control in North-West Europe involved a large number of radar units. 83 and 84 Groups of the Second Tactical Air Force would each have four Ground Control Intercept (GCI) / Forward Director Post (FDP) radar units, with the Type 15 / 11 / 13 radars, and four Type 6 Light Warning sets. 85 Group, protecting the rear areas, would have six GCI radars and four sets dedicated to low-level and surface coverage over the sea. All would be supported by Wireless Observer Units - RAF personnel visually detecting and reporting aircraft at the front line – and a Mobile Signals Servicing Unit, who would undertake repairs beyond the ability of each radar unit’s technicians. Space limitations affected the planned build-up of these units ashore: firstly, shipping radar units competed for space with food, ammunition and fuel; secondly, the physical space (and associated radio and radar frequency separation) of the beachheads necessitated a gradual build-up to full strength. The first radars were to land in the late morning of D-Day and be operational at their inland sites that night.

Map showing the planned deployment of the ground-based air command and control system in the first 9 days after D-Day. (Crown Copyright)

More units were to arrive over the following days to complete the entire system by 2nd July 1944. All the units travelled first to the concentration area at Old Sarum, Wiltshire, before being called forward to their embarkation areas beside the south coast ports and then onto their transport ships, usually Landing Craft (Tank), for the crossing to France.

A Successful Landing on Gold Beach

While all the operators and technicians involved deserve praise for their hard work in dangerous conditions, the first mobile radar units which landed on D-Day were exposed to the most ‘risk and rigour’. Both lead units, 15083 and 15082 GCI, had the Type 15, 11 and 13 radars, radios and domestic equipment with their 27 vehicles. The Unit strengths were around 180 personnel.

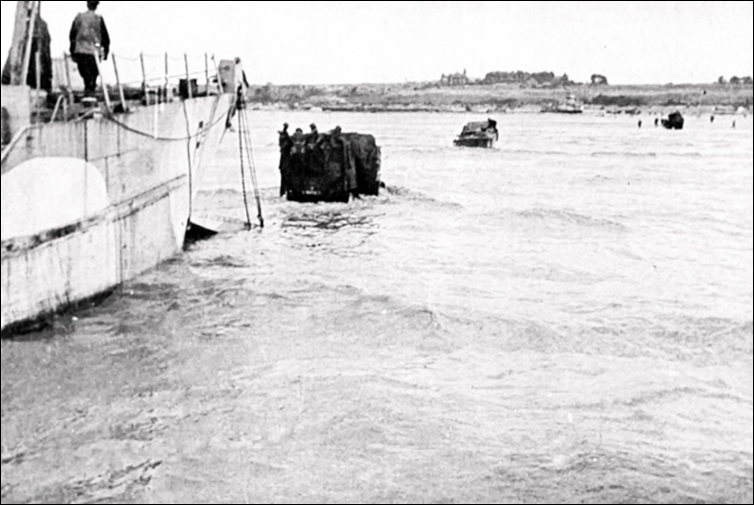

15083 GCI, in the British Sector, made a successful wet-shod landing on Gold beach in the early afternoon on D-Day. The Royal Navy crews of the LCTs did a sterling job delivering the radar convoy onto the correct beach, but one of the radar antenna vehicles then became bogged in wet sand and had to be towed out with tractors.

Vehicles of 15083 GCI completing their wet-shod landing on King Red sector of Gold Beach, 6 June 1944. (Crown Copyright)

The convoy moved to its assigned area at Meuvaines, two miles south-east of Arromanches, and was operational by late evening on D-Day with its Type 11 radar; faults in the other radars would be fixed by the following day. The only issue was that the RAF Mobile Signals Unit assigned to work with them were landed on the wrong beach and had to wait for the route to the radar site to be cleared. Such problems were to be expected in an amphibious landing on a hostile shore!

A Delayed and Dangerous Landing on Omaha Beach

By contrast, the radar unit assigned to the American Sector, 15082 GCI, had a traumatic landing in the most trying of circumstances on Omaha Beach. They embarked in five LCTs in Portland on 2nd June, and arrived off the beach opposite Colleville-sur-Mer at daybreak on 6th June. The first attempt to land at 1130 was turned back; the beach was still under enemy machine-gun and shellfire, and it would have been impossible to land a heavy vehicle convoy in these conditions. A second attempt was made at 1700, the LCTs having been ordered to land their personnel and equipment come-what-may. As the LCTs approached the new landing beach opposite Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, they observed that American vehicles lined up to exit the beach were being destroyed by enemy 88mm guns, causing blockages to the exits from the beach. Many of 15082’s vehicles were landed in over 4’ of water, which was manageable, but some found that they had been landed on a sandbank when they drove into what turned out to be 6’ of water further inshore, ‘drowning’ the vehicles and forcing the crews to swim for dry land. Vehicles that did make it to shore were moved up the beach towards the Les Moulins draw, but more of them were destroyed by enemy fire from 88mm guns. In total, only eight of the unit’s 27 vehicles made it to the top of the beach. Unable to move further, unit personnel spent the remaining hours of daylight helping the wounded on the beach and salvaging what equipment they could.

Omaha Beach late on D-Day. Beyond the bogged down Sherman tank in the foreground lie burnt-out and damaged vehicles from 15082 GCI. (US Naval Archive 80-G-45714)

Casualties on Omaha

From their landing at 1700 until nightfall, the unit lost one officer and nine other ranks, with a tenth dying of his wounds the following day. The circumstances of the death of the unit’s 22-year-old controller, Flt Lt Douglas Highfield, were recalled later by Flt Lt Rycroft, the Medical Officer, and his driver, LAC Cubitt. Flt Lt Highfield was assisting Squadron Leader Victor Harrison, who had lost a foot in an explosion, when they heard another incoming shell. Highfield threw himself over Harrison to protect him and was killed by the explosion. Five of the men lost were from the accompanying Royal Signals detachment who were to provide communications for the radar unit. In addition to the deaths, five of the unit’s officers and thirty-one other ranks were wounded. In total, over a quarter of the unit were casualties in the landing. The following personnel lost their lives:

Flt Lt Highfield

Cpl Day

Cpl Middleton

LAC Newson

LAC Parr

LAC Routledge

Signalman Attrill

Signalman Baldry

Signalman Ellis

Signalman Grotier

Signalman Peckett

All are buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Bayeux.

Recovery

Having moved US and British wounded off the beach, the remaining 15082 personnel and vehicles sheltered for the night beside low walls lining the road into the village of Les Moulins, just off the beach. The following morning, the 7th June, as the road beyond Les Moulins became slightly less hazardous from enemy fire, they moved inland to avoid 88mm shelling which was still targeting the beach area. The next few days were spent moving from holding area to holding area, often sheltering in foxholes from the intermittent but regular enemy fire. A suitable radar site in the small Omaha beachhead was eventually located on the 9th June. In the intervening few days, the Unit’s technical staff had worked wonders, repairing one of the radars, allowed the radar station to go ‘on the air’ on the night of the 10th-11th June 1944. In the days that followed, replacement personnel and equipment would arrive from the UK and in the next month 15082 GCI would control allied fighters leading to the destruction of 22 enemy aircraft.

Gallantry Awards

The men of 15082 GCI were awarded the following gallantry medals for their action on D-Day:

Military Cross:

Sqn Ldr Trollope (Officer Commanding)

Sqn Ldr (Reverend) Harding (Padre)

Sqn Ldr Best (Unit Equipment Officer)

Flt Lt Rycroft (Medical Officer)

Military Medal:

FS Ekersall (Equipment FS)

LAC Reid (Medical Orderly)

Croix de Guerre:

FS Adair (Equipment FS)

FS Muir Adair was separated from the unit on landing and subsequently led a scratch group of multi-national personnel fighting their way through enemy defences to rejoin his colleagues.

Afterword

Numbers 15082 and 15083 GCIs were joined by a range of other radar units and operations rooms in the days and weeks after D-Day. They would follow the Allied armies as they advanced across North-West Europe, providing radar surveillance, air raid warning and aircraft control against an ever-decreasing enemy air threat, demonstrating the benefits of a ground-based air command and control system to expeditionary operations on land, a lesson which is just as valid today.

If you would like to read more about these units on D-Day, we can recommend:

21 Base Defence Sector at Omaha Beach

References:

21 (Base Defence) Sector RAF at Omaha Beach Website.

Air Ministry, Shore Radar Services, Oct 1944

Off to War with ‘054’ by John Kemp.

RAF Air Historical Branch Study, Signals Volume IV, Radar in Raid Reporting.

RAF at Omaha Beach website, Peter Best.

Supplement to the London Gazette – 14 November 1944

The National Archives: 21 (Base Defence) Sector Operations Record Book, AIR 26/40/1

The National Archives: Air Signals Report on Operation “Neptune”. Planning and Assault Phase, July 1944. Report on the Employment of British Ground Radar During and Immediately Following the Assault. AIR 20/4395