This year marks the 80th anniversary of important events in the Second World War. Against the backdrop of the Allied victories in 1943 across North Africa and the Mediterranean, the predecessors of RAF Boulmer’s Air Battle Managers, Engineers and Technicians led the development of expeditionary radar surveillance and control. In the first of three articles this summer, 20 Squadron’s resident historian looks back at a fascinating period of rapid progress.

Most of us are aware of the key part played in the Battle of Britain by radars and Air Chief Marshal Dowding’s command and control system, without which the Battle would have been significantly more difficult for RAF Fighter Command. While the defence of the United Kingdom was the highest priority, the RAF was also planning for air surveillance and control worldwide.

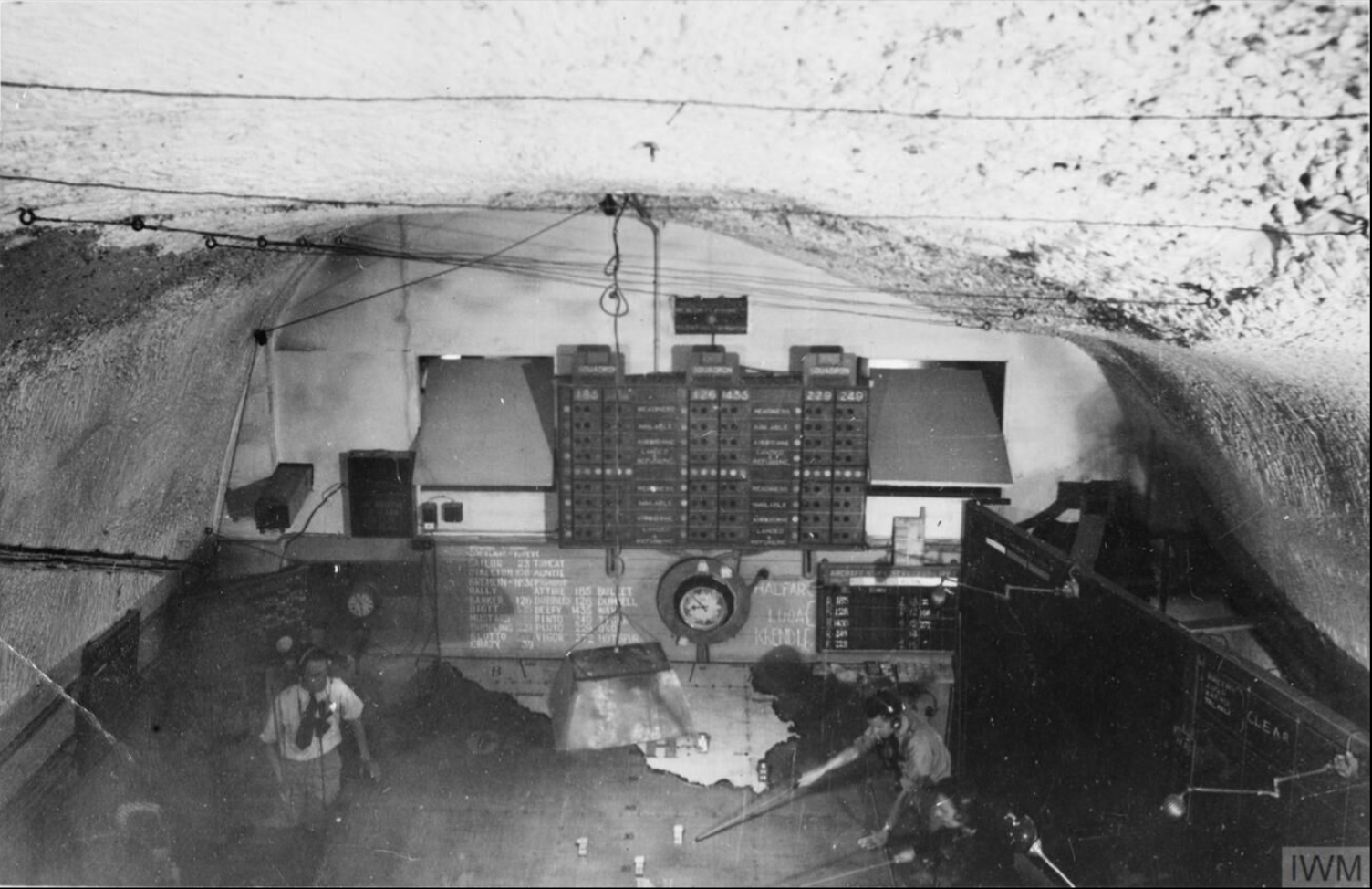

In the Mediterranean theatre, the RAF needed to build air surveillance and control units in locations for which it had responsibility, such as Gibraltar, Malta and Egypt. These would be built along the same lines as the system in the United Kingdom. Static ‘Chain’ radars for long-range early warning and shorter-range, low-level coverage would be linked to a Filter Room, which would produce an air picture to enable fighters to be controlled from a Group or Sector Operations Room.

Number 8 Sector Operations Room, Lascaris War Rooms, Valetta, Malta. © IWM HU 38344

In Egypt particularly, building such a system presented difficulties. The Middle East Air Force had to compete for equipment with the expanding system in the United Kingdom. When assigned, equipment had to be adapted for overseas, modifying the condensers, wiring and cooling systems for hotter temperatures and the presence of blowing sand and dust. Trained personnel were slow to arrive, as they were also need urgently at home. The timber for the radar towers could only be sourced from Canada or Australia, adding further delays to construction. Unlike the United Kingdom, Egypt did not possess a country-wide telephone system into which the radars and ops rooms could plug in order to exchange information. So all communications between sites had to be by radio, with the complexity of multiple, changing frequencies. Yet despite these difficulties, the air surveillance and control system in Egypt took shape and, with the resident fighter squadrons, turned back several German and Italian raids.

The Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre of War © Crown Copyright

To defeat the Axis powers in the Mediterranean would also require expeditionary operations, with the RAF supporting the Eighth Army, either across the deserts of North Africa or through amphibious landings. Throughout the RAF, radar-based air surveillance and control was now widely accepted as a pre-requisite for successful air operations, and thus radars and operations rooms would need to keep up with an advancing (or retreating) army.

The first ‘mobile’ radar sent to theatre was the Type 9 Mobile Radar Unit. Comprising 13 heavy vehicles to haul the radar equipment, two collapsible 105’ towers for the antenna and 60 personnel, it could detect aircraft as far as 150 miles, depending on the height of the aircraft. However, it took up to two days to become operational after arriving at a new site, which made it less than ideal for following a rapidly moving army!

A Type 9 Mobile Radar Unit, pictured here in the UK © Crown Copyright

A smaller, truly mobile set was required, and the radio branch of the Middle East Air Force developed one from an Air-Surface Vessel radar mounted on a Wellington bomber. With a new antenna designed locally, the original Type 6 Light Warning Radar could be carried in a single small lorry, and even broken down into pack loads for mules or camels. The radar could be operated continuously by a crew of as few as ten personnel and could be operational within 30 minutes of arrival at a new site. Although its maximum range was around 50 miles, its mobility meant that it could operate safely within about ten miles of the front.

A Type 6 Light Warning Radar, c/o History Link 101

To complete the ‘layering’ of the detection capability, Wireless Observer Units (WOU) were formed. A version of the Royal Observer Corps staffed by Regular RAF personnel, they operated from jeeps equipped with radios, and called in sightings of friendly and enemy aircraft from a position a few miles behind the front. All radar and WOU sightings were radioed back to a mobile Air Warning Centre, who fused the information into a single air picture. Mobile Operations Room Units, akin to Sector Control, received this picture by radio and controlled friendly fighters from their own map tables. Through hard work and fine tuning of procedures throughout the campaign, a radar return or WOU sighting could reach a controller’s table in less than 30 seconds.

A typical RAF Mobile Operations Room – this one belongs to 13 Squadron in Canrobert, Algeria.

© IWM CNA 114

The headquarters of a Wireless Observer Unit in the Western Desert – sightings from jeeps would have been radioed through these small HQs before being sent onwards to the Air Warning Centre for filtering. © IWM CM 2425

The radars, in particular, achieved prodigious feats during the campaign. On two occasions, Light Warning Radar units were airlifted into recently captured airfields, where the crew carried their equipment through nearby minefields to high ground, and were operational within 30 minutes, providing vital early warning of enemy air attacks. At Cap Serrat in Tunisia, two radar units crawled their way through forest and bog to operate from the lighthouse compound for three weeks, providing early warning of Axis resupply flights into Tunis. During the period, they could only operate at night as they were overlooked by Axis ground units on high ground, were subject to 67 air attacks, and suffered almost constant shortage of food and water.

The airfield at ‘Marble Arch’ in the Western Desert. One Light Warning Radar was airlifted in on the morning after its capture to provide early warning of enemy air activity. © IWM CM 4231

The RAF in North Africa had re-created the sophisticated Dowding System for air surveillance and control in a very mobile form in a very short time in an overseas theatre. When the North African campaign finished with the capture of Tunis in May 1943, the Middle East Air Force had established a chain of static radar sites to protect the North African coast from Egypt to Morocco. It also had a range of mobile radar, wireless observer and operations room units which were ready for further expeditionary action as the Allies started planning for Operation HUSKY, the invasion of Sicily, which we’ll look at next time.